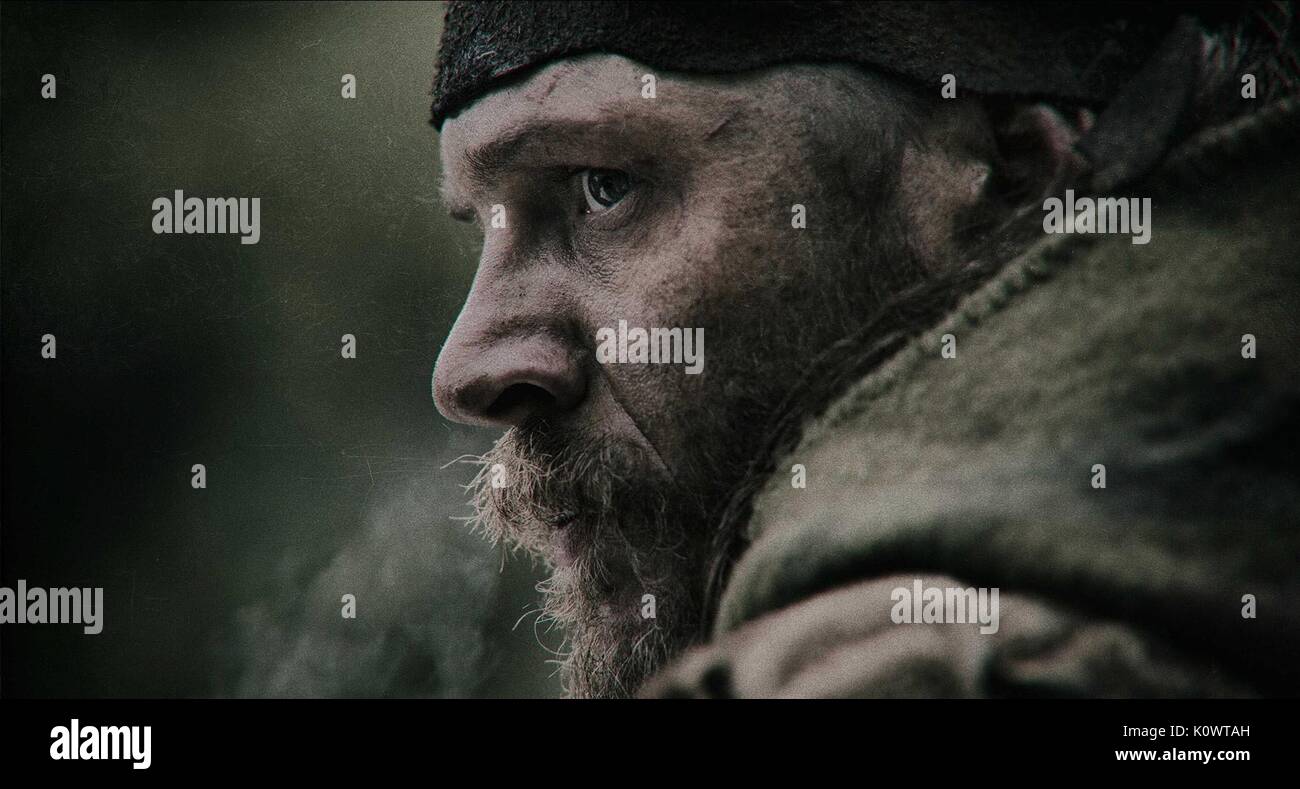

Movie The Revenant 2015

Watch The Revenant on 123movies: While exploring the uncharted wilderness in 1823, legendary frontiersman Hugh Glass sustains injuries from a brutal bear attack. The revenant the revenant 2015 survival revenge bear attack native american nature putlocker 9movies yesmovies 123movies solarmovie. Subscribe to the www9.0123movies.com mailing.

In “The Revenant,” a period drama reaching for tragedy, Leonardo DiCaprio plays the mountain man Hugh Glass, a figure straight out of American myth and history. He enters dressed in a greasy, fur-trimmed coat, holding a flintlock rifle while stealing through a forest primeval that Longfellow might have recognized. This, though, is no Arcadia; it’s 1823 in the Great Plains, a pitiless testing ground for men that’s littered with the vivid red carcasses of skinned animals, ghastly portents of another slaughter shortly to come. The setting could not be more striking or the men more flinty.

“The Revenant” is an American foundation story, by turns soaring and overblown. Directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu (“Birdman,”“Babel”), it features a battalion of very fine, hardworking actors, none more diligently committed than Mr. DiCaprio, and some of the most beautiful natural tableaus you’re likely to see in a movie this year. Partly shot in outwardly unspoiled tracts in Canada and Argentina, it has the brilliant, crystalline look that high-definition digital can provide, with natural vistas that seem to go on forever and suggest the seeming limitless bounty that once was. Here, green lichen carpets trees that look tall enough to pierce the heavens. It’s that kind of movie, with that kind of visual splendor — it spurs you to match its industrious poeticism.

If you’re familiar with Mr. Iñárritu’s work, you know paradise is generally short-lived, and here arrows and bullets are soon flying, bodies are falling and the muddy banks of a riverside camp are a gory churn. Glass, part of a commercial fur expedition, escapes with others on a boat and sails into an adventure that takes him through a crucible of suffering — including a near-fatal grizzly attack — that evokes by turns classics of American literature and a “Perils of Pauline”-style silent-film serial. Left for dead by two companions, Glass crawls out of a shallow grave and toward the men who abandoned him. It’s a narrative turn that suggests he, like so many before him, is one of D. H. Lawrence’s essential American souls: “hard, isolate, stoic and a killer.”

The movie is partly based on “The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge,” a 2002 historical adventure by Michael Punke inspired by the real Hugh Glass. In 1823, Glass signed on with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company for an expedition on the upper Missouri River that almost did him in when Arikara Indians attacked the group and, sometime later, he was mauled by a grizzly sow that may have been protecting her cubs. The bear should have killed Glass. Instead, its failure to do so — along with Glass’s frontier skills, some help from strangers and the indestructible romance of the American West — turned him into a mountain man legend and the inspiration for various accounts, including a book-length poem and a 1971 film, “Man in the Wilderness.”

Motivated and eligible students can choose to take their GED® preparation courses online from the comfort of their own home or at any of City Colleges'. City colleges of chicago ged classes.

Mame full set. The latest MAME version number is always shown in the official MAMEdev change log. If you download the split set of MAME ROMs then you do not need to. Sep 11, 2018 - The latest MAME ROMSET (requires version of MAME to play – download from MAMEDEV) is sporting some huge.

The historical Glass was somewhat of a question mark, which makes him a spacious vessel for interpretation. Mr. Iñárritu, who wrote the script with Mark L. Smith, fills that vessel to near overflowing, specifically by amplifying Glass with a vague, gauzily romantic past life with an unnamed Pawnee wife (Grace Dove) seen in elliptical flashback. By the time the movie opens, the wife is long dead, having been murdered by white troops, and Glass’s son, Hawk (Forrest Goodluck), has become his close companion. The son’s name evokes James Fenimore Cooper’s Hawk-eye (“The Last of the Mohicans”), and together Glass and Hawk create an intimate, familial bulwark — and a multicultural father-and-son dyad — in a wilderness teeming with assorted savages.

Who exactly the savage is here is never much of an issue; as a sign scrawled in French spells out in one scene, everyone is. Mr. Iñárritu likes big themes, but he isn’t given to subtlety. There’s a shocker of an image, for instance, in “Amores Perros,” his feature debut, which expresses his talent for finding the indelible cinematic shot, the one you can’t look away from even when you want to, and also underscores his penchant for overstatement. One of those multi-stranded stories that he helped repopularize (“Babel,” etc.), “Amores Perros” includes a murder capped by the vision of human blood spilled on a hot griddle. This being a big moment as well as an illustration of Mr. Iñárritu’s sensibility, the blood doesn’t just splatter, it also sizzles. It’s filmmaking as swagger.

I thought of that artfully boiling blood while watching “The Revenant,” with its butchered animals, muddled ideas, heart-skippingly natural landscapes and moment after moment of visual and narrative sizzle. What makes too many of his moments, ghastly and grand — an arrow piercing a man’s throat, the beatific face of a beloved, a man scooping the innards out of a fallen horse, the enveloping softness of the dusk light — isn’t the moment itself, but that little something special that he adds to it, whether it’s a gurgle of blood in a throat or the perfectly lighted sheen of a hunk of offal. Mr. Iñárritu isn’t content to merely seduce you with ecstatic beauty and annihilating terror; he wants to blow your mind, to amp up your art-house experience with blockbusterlike awesomeness.

Sometimes, as with “Birdman,” Mr. Iñárritu’s last movie, this desire to knock the audience out pays off. “The Revenant” is a more explicitly serious, graver and aspirational effort. Working again with a team that includes the director of photography Emmanuel Lubezki (whose credits include “Birdman”) and a handful of special-effects companies, Mr. Iñárritu creates a lush, immersive world that suggests what early-19th-century North America might have looked like once upon an antediluvian time. Yet he complicates the myth of the American Eden — and with it the myth of exceptionalism — by giving Glass an Indian wife and mixed-race son. It’s a strategic move (and another bit of sizzle) that turns a loner into a sympathetic family man. It also softens the story. Instead of another hunter for hire doing his bit to advance the economy one pelt at a time, Glass becomes a sentimentalized figure and finally as much victim as victimizer.

From Davy Crockett to Kit Carson, the mountain man has long had a hold on the American imagination and recently made a revisionist appearance in the form of Katniss Everdeen, the heroine of “The Hunger Games.” The mountain men in “The Revenant” are drawn along more traditional and masculine lines, from their bushy beards to the buckskins and bulky furs that at times make them look almost indistinguishable from the animals they kill. Mr. Iñárritu is entranced by this world, with its glories and miseries, its bison tartare and everyday primitivism, which he scrupulously recreates with detail and sweep. He’s particularly strong whenever Glass, employing that old can-do pragmatism, goes into survivalist mode to cauterize a wound, catch a fish or find shelter.

But Mr. Iñárritu blows it when he moves from the material to the mystical and tries to elevate an ugly story into a spiritual one, with repeated images of a spiral and even a flash of homespun magical realism. Worse, he makes Glass not just a helpless witness to a murder that’s a stand-in for the genocide of the Indians, but also a proxy victim of that catastrophe. It’s disappointing in a movie that offers much and that actually points to another foundation story that emerges when one of Glass’s companions, Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy), tries and fails to get paid for his labor. He learns too late that the system that turns people and animals into commodities is rigged against men like him. And while the simple facts of that system may be too brutal to feed the ambitions of a movie like “The Revenant,” we know that the system nevertheless helped build a nation.

“The Revenant” is rated R (Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult companion). Intense, at times graphic violence, including scenes involving animals. Running time: 2 hours 36 minutes.

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Entertainment grade: B–

History grade: C–

This article contains spoilers.

Hugh Glass was a frontiersman working in the upper Missouri river area in the early years of the 19th century. On a fur trapping expedition in 1823, he was attacked and mauled by a grizzly bear.

Violence

Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) is one of a group of men finishing up a fur trapping expedition in the wilderness. They are attacked by Ree (Arikara) warriors. Whoosh! Someone gets impaled on a spear. Bang! Someone gets shot off his horse. Crack! Someone’s bones shatter. There’s an unflinching close-up of an arrow thwacking into a face, a gun butt bashing into a face, a flying kick to a face. A horse gets shot in the face. It’s exceptionally well choreographed and filmed.

The Revenant review – gut-churningly brutal, beautiful storytelling

This scene is based on a real-life incident: William H Ashley and Andrew Henry (the latter played by Domhnall Gleeson in the film) set up the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1822. In June 1823, Ashley’s band of around 70 men was attacked by Arikara warriors – they estimated around 600, though in the film it’s more like a dozen. Various accounts suggest that between 12 and 18 of Ashley’s men were killed.

Characters

In the film, 10 men get away. Among them are Captain Henry, Glass, Glass’s son Hawk (Forrest Goodluck) and trappers John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) and Jim Bridger (Will Poulter). They have a conversation, but it’s all so extravagantly mumbled that it’s hard to work out what’s going on. Fitzgerald is fighty and racist, so he’s the baddie. Glass is the goodie, because he loves his son (who is half-Pawnee) in a gruff, manly way that involves telling him off a lot. The backstory about Glass’s love for a Pawnee woman is fiction. It has been suggested the real Glass had such a relationship, but there’s no firm evidence – and no evidence that he had any children.

Wildlife

As the men make their way through a forest, Glass happens upon two bear cubs and their angry mama. If you felt wan after the face-smashing scene at the start, reach for the smelling salts. Chomp! Growl! Shake! The bear sniffs him to see if he’s dead, then jumps up and down on his back. Splinter! Howl! Slash! Glass shoots the bear. That really gets on its wick. It tries to rip his throat out. He stabs it in the neck. It flops on him and dies heavily, squishing him like a punctured bouncy castle full of blood.

The cinema audience is by this point laughing, half in horror and half because the scene goes on for so long that it becomes comical. Play black ops 2 on computer. Anyway, while historians are not certain of the precise details, the real Glass did get into a fight with a real bear, some time in August 1823.

Murder

The men find Glass in a rum old state. Captain Henry pays Fitzgerald, Bridger and Hawk to stay behind until it is time for Glass’s inevitable burial. When the captain leaves, Fitzgerald tries to bump Glass off. Hawk interrupts, so Fitzgerald bumps him off instead. This didn’t happen in real life, because Hawk didn’t exist. In the film, the ailing Glass sees Fitzgerald kill his son, giving him an extra motivation to stay alive and seek revenge. When Fitzgerald persuades Bridger to bury Glass alive and abandon him, you know Glass isn’t going to go quietly.

Survival

Movie The Revenant 2015 Was Filmed Where

The real Glass survived his abandonment and dragged his battered body over hundreds of miles of terrain in pursuit of the men who left him for dead. Though he could read and write, Glass never set his story down in his own hand. It was first published by another writer in The Port Folio, a Philadelphia journal, in 1825. It may well have been embroidered then. It has been embroidered many times since.

Hardship

The film has invented some extra obstacles for Glass: it is snowing throughout, even though in real life his trek took place between August and October; the Arikara track him and chase him into a tree; he has to hollow out a dead horse to make himself a sleeping bag. It’s brilliantly filmed, but the characterisations and dialogue don’t match the sophistication of the visuals. Moreover, by the second lingering closeup of a horse’s eye or the sixth epic landscape shot with four-fifths sky and one-fifth land, even those sophisticated visuals begin to feel repetitive. As for the ending, it has been changed in one significant way: in real life, nobody got killed.

Watch Online Movie The Revenant 2015

Verdict

Movie The Revenant 2016

The Revenant is an impressive film inspired by Glass’s real-life story, but lays it on a bit thick and ends up curiously unmoving. The whole thing is begging to be sped up into a two-minute YouTube video set to Benny Hill music.

Related News

- Abcd2 Full Movie Hd

- Mitchell Ondemand 2015 Torrent Tpb

- Download Film Final Destination

- Murder Of Notorious Big

- Watch Detective Conan Gogoanime

- Schedule 1 Drugs List

- Watch Infinite Stratos 2

- Border Police Jobs

- Link Untuk Download Film Indonesia

- Valentino Rossi 2018

- Download Resident Evil 6 Pc

- The Handmaid's Tale Ebook Torrent

- Jodha Akbar Tamil Full Movie

- Download Novel Terbaru

- Killer Bean Unleashed Mod Apk

- Free Download Zip Compressed Folder Opener

- Best Usb Memory Stick For Music

- Hindi Input For Windows 10

- Minecraft Full Version Free Download

- Mortal Kombat X Pc Download

- Keygen For Autocad 2012

- Bokep Jepang Menantu Dengan Mertua

- Personal Brain

- Yaad Teri Aati Hai Mp3

- Secret Games Movie Online

- Google Terjemahan Pdf

- Fsx Deluxe Product Key

- Resident Evil 7 Unlockables

- Walmart Employee Handbook 2018

- Sql Data Compare Script Servers

- Download Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 6

- Autocad 2010 Activation Code Generator